|

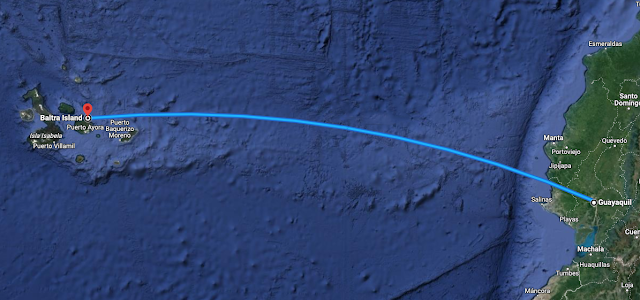

| Straight out over the Pacific |

I had been concerned (based on Gate 1’s luggage restrictions of one carry-on and one checked bag) that we would be flying on a small plane like the one we took to the Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica. Not that I have issues with small planes; it can just be tight with heavy or large carry-on like my camera bag when it is fully loaded. But, it was a regular commercial jet with roomy seats and ample overhead space.

Even though I had done some research in advance, I was surprised at how dry and flat Baltra was. It’s basically just a lava shelf. Of course, its flatness is why one of the only two airports in Galápagos is there.

|

| Arriving in Baltra |

Arrival in Galápagos is arduous because of the massive protections in place to protect the Islands’ fragile ecosystems and wildlife. The plane was sprayed with insecticide before we landed. Then, even though we were flying from Guayaquil in Ecuador to Galápagos in Ecuador, we had to go through passport control.

Our bags, which had been x-rayed and inspected before departure were x-rayed and inspected again. We had heard that they also had dogs that sniffed luggage. I didn’t see any, but we didn’t have eyes on luggage at all times.

Once we cleared “immigration,” we had to wait in line for a public shuttle bus that would take us to the southern part of Baltra, about three miles away.

|

| The path to the shuttle; Photo: Scott Stevens |

While waiting for the bus, I saw my first Galápagos wildlife: My 1,000th bird, a Medium Ground-finch that refused to pose nicely …

|

| Finally! |

… a beautiful Galápagos Dove that did cooperate …

… a Monarch butterfly …

|

| Galápagos is supposed to have lots of Butterfly species; we didn't see that many |

… and a beautiful golden-colored Galápagos Land Iguana resting under a bench ...

Off to a good start.

After the short bus ride past lava field and cactus, we got into another line to wait for a passenger ferry to take us to Santa Cruz Island – a 20 minute-or-so wait for a two-minute trip.

|

| Santa Cruz was greener |

On the other side, we boarded our private Gate 1 minibus and met our local naturalist/guide, Maria José, who didn’t do much guiding this day, but did when we returned to Santa Cruz on our way back to the mainland.

I suspect, however, that she managed all the buses, drivers and ferries for us.

|

| Our route |

Next, we were traveling to Puerto Ayora on the south side of Santa Cruz Island to board the boat that would take us to Isabela.

We were staying the next three nights at the Scalesia Lodge on Isabela.

We had been cautioned (when booking and by Wilson) that the trip could be rough; Wilson had even cautioned us to eat a light breakfast.

Therefore, it seemed odd to stop at a small restaurant (I think it just catered to tour groups because we were the only ones there) …

… for a full lunch including delicious blackberry juice, fish, rice and banana cake ...

|

| Fish and rice was our most frequent meal |

So, with full tummies, we headed on toward Puerto Ayora. When we were almost there, we had a bit of an emergency, when Wilson discovered that he had left his phone at the restaurant. So, somehow, he got a ride back, got his phone and met us at the dock. Of course, he was teased a bit for the rest of the trip!

It was crowded at the dock and we had to wait awhile. But, there was entertainment!

|

| Rays and baby Sharks of the pier |

|

| Lots of boats; Top Photo: GalapagosPRO |

Then, we boarded a tiny, partially covered canoe-like boat (a panga) that I thought was going to be our transportation for the two-to-three-hour trip to Isabela. Yikes!

But, that boat turned out to be a water taxi that took us to a slightly larger, more enclosed boat that would take us to Puerto Villamil on Isabela Island.

I haven’t mentioned it, but it needs to be said: it was hot. Very hot. Very, very hot.

|

| Not much of a view |

And, the boat was enclosed with a canvas sides with plastic windows, making it pretty steamy.

The boat reminded me of a smaller version of a boat I took to Tulum a few years earlier when I went on a cruise with high school friends (I got very, very wet on that boat). So, I understood why it was sealed up in the sides.

But, it was not comfortable. There was a back bench, but all the seats were taken by the time I got on. So, I was prepared to sweat it out.

Before we left Colorado, I had gotten a prescription for Ondansetron, an anti-nausea drug to deal with either traveler’s stomach or motion sickness. I took one before we departed and – considering that it eventually got quite rough – it worked very well. I offered one to Scott, but he declined.

|

| My experience in Tulum |

For most of the trip I didn’t see any birds, but toward the end, I did. I couldn’t see well enough for positive ID; some were probably Petrels and Shearwaters. One was either an Albatross or a Booby; I think a Nazca Booby, which would be a Lifer, but I’ll never know.

The trip was long, fast and increasingly rough.

Very, very rough and overcast with threatening skies by the time – about three hours later – we reached Isabela. Scott had given me his back bench seat about two hours in and, indeed, I did get wet.

I was relieved, however, that, despite being hot in an enclosed boat, I did not get queasy. At all. That medication is great. I need to get some more.

Scott, however, was pretty green when we arrived.

I have read that during the wet/rainy season (Galápagos is opposite the mainland; it was the dry season when we went), transport from Baltra to Isabela is by plane. I am not sure why this process it used. It is not comfortable and it takes forever. On a slower, better boat, you could sight-see and take photos. On a plane, you could get there quickly. If I go back to Galápagos, I will definitely look into how one gets around.

But, regardless, we made it to our Galápagos base.

|

| At Isabela's Puerto Villamil dock |

About the Islands

I talked a bit about Galápagos in my first post, but there is so much more to tell. So, let’s do that now.

As I mentioned, my first impression of Baltra was that it was a lava shelf.

|

| Lava everywhere |

That’s because the Galápagos Islands have experienced continuous volcanism for at least 20 million years, possible more.

|

| A map of the islands in Puerto Villamil |

Eruptions created 21 rugged islands and scores of islets and rocks that sit above the Nazca fault and the Galápagos hotspot.

The fault is moving to the east/southeast, diving under the South American Plate at a rate of about 2.5 inches per year.

The hotspot is where the Earth's crust is being melted from below by a mantle plume.

The first islands formed at least 8 million and possibly up to 90 million years ago (that’s quite a spread, but scientists learn new things every day).

There are 13 active volcanoes on the archipelago. The most recent eruption was Volcán Wolf (Wolf Volcano) on the north spur of Isabela Island, which started in January 2022.

|

| The 2022 Volcán Wolf eruption; Photo: Reuters |

Unlike Hawai’ian volcanoes, Galápagos’ are tall and rounded, indicating continuing recent activity. Volcanoes at the west end of the archipelago are tholeiitic basalt and are taller and younger with well-developed calderas. Those on the east are shorter, older, lack calderas and have a more diverse composition.

Older islands have disappeared below the sea as they moved away from the mantle plume, but the youngest, Isabela and Fernandina, are still being formed.

The largest of the islands, Isabela, where we stayed, measures 2,250 square miles and makes up close to three-quarters of the total land area of the Galápagos. Albemarle is Isabela's English name; all the islands have English names, but you seldom hear them used, except for Darwin.

|

| Our base |

Volcán Wolf is the highest point, with an elevation of 5,600 feet above sea level. The island was named in honor of Queen Isabella I of Castile. Isabela’s seahorse shape is the product of the merging of six large volcanoes into a single land mass. The third-largest human settlement of the archipelago, Puerto Villamil, is located at the southeastern tip of the island.

The other main islands we visited were:

Baltra (South Seymour) and Santa Cruz (Indefatigable).

|

| Left, Baltra, photo: Scott Stevens; Right, Santa Cruz |

Baltra owes its flat topography to geologic uplift rather than an eruption. During the 1940s, scientists moved 70 of Baltra's Galápagos Land Iguanas to neighboring North Seymour Island as part of an experiment. This saved the day when the Iguanas left on the island died out as a result of the island's military occupation in World War II. In the 1990s, Iguanas were reintroduced to Baltra.

Santa Cruz which hosts the largest human population in the archipelago in the town of Puerto Ayora and is home to the Charles Darwin Research Station, the headquarters of the Galápagos National Park Service and a breeding center where Tortoises are hatched, reared and reintroduced to their natural habitat.

Other Islands that we did not visit are:

|

| Nope! Photo: eBird |

Bartolomé (Bartholomew) is a volcanic islet with populations of Galápagos Penguins, the only wild Penguin to live on the equator.

Darwin (Culpepper) is far removed from the rest of the archipelago and reached only via SCUBA tours. It was famous for Darwin's Arch, a natural formation a half mile from the island, but the arch collapsed in 2021.

Española (Hood) is the oldest and southernmost island. Because of its remoteness, it has a large number of endemic species.

Fernandina (Narborough) is the youngest and westernmost island.

|

| PO barrel; Photo: GoGalapagos |

Floreana (Charles or Santa María) was one of the earliest to be inhabited. At Post Office Bay, 19th-century whalers kept a wooden barrel where mail could be picked up and delivered by passing ships.

Genovesa (Tower), the remaining edge of a large submerged caldera, has large bird populations.

Marchena (Bindloe) is home to Galápagos Hawks, Sea Lions and the endemic Marchena Lava Lizard.

|

| Magnificent Frigatebird |

Islands that celebrate Christopher Columbus, who may have more things named after him than anyone else on Earth, are Pinzón (Duncan) and Pinta (Louis). The Pinzón brothers were the captains of the Pinta and Niña.

Rábida (Jervis) has a high amount of iron in the lava, giving it a red color.

San Cristóbal (Chatham) was the first island Charles Darwin visited during his voyage and has the largest freshwater lake in the archipelago.

|

| Young Palo Santo tree |

Santa Fe (Barrington) has a forest of palo santo trees and opuntia cactus, which are a super large species of prickly pear.

Santiago (San Salvador, James) was seriously damaged by human-introduced pigs and goats that were finally eradicated by the Park Service in 2002 and 2006, respectively.

Wolf (Wenman) is home to the Vampire Finch, which feeds partly on blood pecked from other birds.

Five of the islands – Baltra, Floreana, Isabela, San Cristóbal and Santa Cruz – are inhabited.

Total Galápagos population has risen from less than 2,000 in 1959 to almost 50,000 today.

Unique Wildlife

The Galápagos Islands are home to a large number of unique species.

|

| CW: Marine Iguana, Santa Cruz Giant Tortoise, Galápagos Sea Lion, Sally Lightfoot Crabs |

Why?

The cold Humboldt Current travels north from South America and the Panama Current travels south from Central America.

They meet at Galápagos, providing the perfect environment for the unique mix of wildlife.

Because the islands were never attached to any continent, Galápagos wildlife arrived in one of three ways: flying, floating or swimming. Once they got there, many species had to adapt to survive, evolving into new endemic species.

It was after visiting the Galápagos and studying the wildlife that a young Charles Darwin developed his theory of evolution.

|

| Charles Darwin as a young and an older man |

One of the best known is the largest land animal on the archipelago is the Galápagos Giant Tortoise.

|

| Santa Cruz Giant Tortoise |

Specialized subspecies, generally specific to an island or even a part of an island, live on seven of the islands and have an average lifespan of more than 150 years.

The Marine Iguana cohabitates with Land Iguanas, Lava Lizards, Geckos and harmless Snakes.

|

| The only Iguana adapted to life in the sea |

|

| The endemic Galápagos Mockingbird |

Of course, I didn’t see anywhere near that many because some are found only on one island and we went to only three islands. Two listed as “standouts” are the Galápagos Penguin, which lives on the colder coasts, and the Flightless Cormorant, a which has lost the ability to fly. We saw neither.

There are an additional 29 species of migrant birds that vary between being both native and/or migratory.

|

| Two familiar birds: Great Blue Heron and Yellow Warbler |

Many species introduced to Galápagos by pirates, including goats, donkeys, cattle and dogs, had major negative impact.

Feral goats destroyed many habitats and, because there were no predators, got quickly out of hand. Goats contributed greatly to the near extinction of the Giant Tortoises.

The larger Galápagos Islands have four ecological zones: coastal, low or dry, transitional and humid.

During the season known as the garúa (June to November), the temperature by the sea is 72°F with a steady and cold wind, frequent drizzles (garúas) and dense fog. During the warm season (December to May), the average sea and air temperature rises to 77°F, there is no wind and it is sunny with sporadic rain.

Well, it looks like we did have the right season for Galápagos.

|

| We had nice weather |

As altitude increases on the large island, temperature decreases and precipitation increases. Vegetation in the highlands tends to be green and lush. Lowland areas tend to have arid and semi-arid vegetation, with thorny shrubs and cacti.

|

| Cactus grows right by the ocean |

There are 500 native and endemic plants plus more than 700 introduced species. When foreign species invade the islands, they can easily proliferate until they are the majority, threatening endemic species. Hence the process we endured entering Baltra.

History

The first recorded visit to the islands happened in 1535, when Fray Tomás de Berlanga, the Bishop of Panamá, stumbled upon the undiscovered land on a voyage to Peru.

|

| Cowley's first map |

The first crude map of the islands was made in 1684 by the buccaneer Ambrose Cowley, who named the individual islands after some of his fellow pirates and some after English royalty and nobility (those Engish names I mentioned).

The group of islands was, appropriately, named "Insulae de los Galopegos" (Islands of the tortoises).

Whether the Incas ever made it to the islands is disputed. Oceanic Pacific islands in the same general area as Galápagos were all uninhabited when discovered by Europeans, with nothing to indicate any prehistoric human activity.

|

| Did he make it? |

A 1952 archaeological dig found artifacts that ”suggested visitation by pre-Columbian South American peoples.” But, a 2016 reanalysis suggested that the artifacts had probably been brought as mementos at the time of Spanish occupation.

|

| Polynesian canoe; Art: Age of Empires |

Lack of fresh water on the islands probably discouraged lengthy stays by anyone who landed on them, except for mostly English pirates who used them to hide out after raids.

In the late 1700s, Galápagos became as base for the Pacific whalers who captured and killed thousands of the Galápagos Tortoises to extract their fat.

|

| Stealing Tortoises; Illustration: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, 1859 |

Because Tortoises can survive for months without food or water, whalers and pirates often took them and kept them alive onboard ships to eat later. This greatly diminished and, in some cases, eliminated certain subspecies. Along with whalers came Fur Seal hunters, who brought that animal close to extinction.

The first known permanent human resident on Galápagos was Patrick Watkins, an Irish sailor who was marooned on Floreana from 1807 to 1809. He survived by hunting, growing vegetables and trading with visiting whalers, before stealing a boat and navigating to Guayaquil.

In 1818, whalers discovered a "mother lode" of Sperm Whales a thousand miles west of the South American coast at the equator. An influx of whaling ships used the Galápagos Islands as a frequent stop for the whalers both before and after visiting what came to be known as the “Offshore Ground.”

|

| Sperm Whale hunting brought more sailers; Engraving: William Page |

Ecuador annexed the Galápagos Islands in 1832, naming them the Archipelago of Ecuador and giving each island a new Spanish name. The older names remained in use in English-language publications.

The first governor of Galápagos, General José de Villamil, brought a group of convicts to populate the island of Floreana, and later, some artisans and farmers joined them.

The survey ship HMS Beagle, captained by Robert FitzRoy, came to Galápagos in 1835 to survey approaches to harbors. FitzRoy and others on board, including the young naturalist Charles Darwin, made observations on the geology and biology on Chatham, Charles, Albemarle and James islands before they left to continue their round-the-world expedition.

|

| HMS Beagle; Engraving: R.T. Pritchett |

Primarily a geologist at the time, Darwin was impressed by the quantity of volcanic craters they saw, later referring to the archipelago as "that land of craters." His study of several volcanic formations over the five weeks he stayed in the islands led to several important geological discoveries, including the first correct explanation for how volcanic tuff is formed.

|

| Darwin's claim to fame |

Darwin noticed the Mockingbirds differed between islands. He collected lots of different Finches from different islands. But, because he didn’t think they were related, he didn’t label them by location.

When Darwin learned that tortoises differed from island to island, he speculated that the distribution of the Mockingbirds and Tortoises might "undermine the stability of species."

When he analyzed specimens of the other birds upon his return to England, he determined that the “different” birds were Finches unique to specific islands.

These facts led to Darwin's theory of natural selection.

Attempts to colonize included setting up operations to collect a type of lichen to be used as a coloring agent and an attempt at growing commercial sugar cane. But, scientific expeditions continued to be the primary reason people came to Galápagos.

During the early 1900s through 1929, cash-strapped Ecuador tried to sell the islands. The U.S. had repeatedly expressed interest because of Galápagos’ strategic position guarding the Panama Canal. Japan and Germany expressed interest and Chile, which had previously acquired the Straits of Magellan and Easter Island for strategic reasons, was interested. Because Chile was alarmed that a U.S. purchase would put its northern provinces within the range of U.S. Navy, Chile lobbied Ecuador to resist U.S. purchase or occupation.

In the 1920s and 1930s, a small wave of European settlers arrived to take advantage of laws that provided colonists the 20 hectares of land, the right to maintain their citizenship, freedom from taxation for the first 10 years in Galápagos and the right to hunt and fish freely. The first to arrive were Norwegians who settled briefly on Floreana, before moving on to San Cristobal and Santa Cruz.

During World War II, Ecuador authorized the U.S. to establish a base on Baltra and radar stations in other strategic locations in order to patrol the Pacific for enemy submarines and to protect the Panama Canal.

After the war, the facilities were given to the government of Ecuador.

In 1946, a penal colony was established on Isabela Island, but it was suspended in 1959.

|

| Almost all of the land is National Park |

Galápagos became a National Park in 1959, the centenary year of Charles Darwin's publication of The Origin of Species.

Tourism started in earnest in the 1960s, imposing more restrictions on the people already living in Galápagos.

More growth came when job opportunities in tourism, fishing and farming attracted poor fishermen and farmers from mainland Ecuador.

In the 1990s and 2000s, fishermen seeking to increase the annual Sea Cucumber quotas initiated violent confrontations with the Galápagos National Park Service, including capturing and killing Giant Tortoises and holding Park Service staff hostage.

The first protective legislation for the Galápagos was enacted in 1930 and supplemented in 1936. It was not until the late 1950s that positive action was taken to control what the devastation that was happening to native flora and fauna.

More than 97.5 percent of the land area, excluding areas colonized before 1959, comprise the National Park.

The Darwin Foundation, which was founded the same year as the Park, provides research findings to the government for effective management of Galápagos.

In 1986, 27,000 square miles of ocean surrounding the islands was declared a Marine Reserve, second in size only to the Great Barrier Reef.

In 1990, the archipelago became a Whale Sanctuary.

UNESCO recognized the islands in 1978 as a World Heritage Site and, in 1985, as a Biosphere Reserve. This was later extended in 2001 to include the Marine Reserve.

In 2007, UNESCO put Galápagos on the List of World Heritage in Danger because of threats posed by invasive species, unbridled tourism and overfishing. In 2010, Galápagos was removed from the list because of significant progress in addressing problems.

Settling In

When we arrived and got off the boat, we were greeted by a group of Marine Iguanas lounging by the welcome sign. When we went by the area the next morning, we saw an even larger group there.

|

| Lovely surroundings; Top photo: Jenny Owen |

After gathering our luggage, we jumped on our dedicated minibus and made the quick drive up to the Scalesia Lodge, which sits of the flanks of Sierra Negra.

Set in lush tropical jungle, the Lodge has a main building with an open-air dining area where we had all of our meals (and did a little birding).

We stayed in individual elevated tent cabins with lovely decks.

|

| The cabins were surrounded by jungle |

They reminded me very much of the game reserves I stayed at in South Africa.

|

| Our cabin |

Because it had taken so, so long to get there, there we really no activities the first day except for a lovely dinner and settling in.

Scott, who thought he was suffering from seasickness, felt progressively worse and ended up spending the entire first night as sick as a dog. It persisted (albeit slightly improved) for the entire trip and caused him to miss the next morning’s activities. Fortunately, he didn’t need me to stay with him. After all, it was bad enough that one person was missing planned activities.

At breakfast, there was a very vocal tiny bird serenading us (and hopping across plates, tables and serving dishes) and I was hoping it was another Lifer.

Later on, I saw two new birds on the grounds …

|

| I saw several Green Warbler-Finches ... |

|

| ... and Common Cactus-Finches (I didn’t ID it until I returned home) |

So that was a long, long day.

I’ll talk about our next morning’s adventures in my next post.

|

| Some good stuff coming up |

Trip date: March 7 - 19, 2023

No comments:

Post a Comment