|

| The Marfa Prada "store" has been there since 2005 |

Our first stop was White Sands National Park. Caty and I have both been there before and I have blogged about it here and here. But, I never provided the full scoop on the Park. So, let’s go ...

A disclaimer, though: Caty and I went only for an evening this time, hoping for (and failing to get) a glorious sunset or to, at least, see some critters.

So, I hardly took any photos.

White Sands National Park covers 227.8 square miles in the Tularosa Basin, including the southern 41 percent of a 275 square-mile field of gypsum sand dunes. The largest of its kind on Earth, the dune field averages 30 feet deep, has dunes as tall as 60 feet and comprises about 4.5 billion short tons of sand.

Approximately 12,000 years ago, the land here featured large lakes, streams, grasslands and Ice Age mammals. As the climate warmed, rain and snowmelt dissolved gypsum from the surrounding mountains and carried it into the basin. Further warming and drying caused the lakes to evaporate and form selenite crystals.

|

| Very white sand made of gypsum |

Strong winds then broke up crystals and transported them eastward. A similar process continues to continually replenish the sand today.

Recently, researchers found multiple human footprints at White Sands buried in layers of gypsum on a large playa.

The prints are bracketed by layers containing seeds radiocarbon dated as between 23,000 and 21,000 years old. Up to the discovery, the consensus for human arrival into North America was placed at 13,000-16,000 years ago. So, if the new data is proven accurate, this could be the most significant evidence of humans found on our continent. Scientists are still examining and debating data.

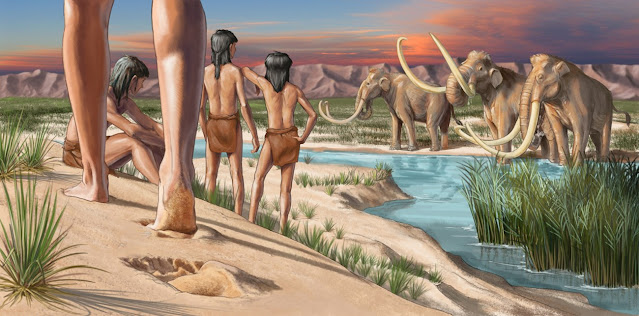

|

| How the prints were made; Illustration: NPS |

It is known that paleo-Indians inhabited the shoreline of Lake Otero, the lake that covered much of the Tularosa Basin. Projectile points, known as Folsom and Plano points, that they made and attached to spears for hunting Columbian Mammoths, Camels, Ground Sloths and Bison have been found in the area.

|

| Arrowheads found at White Sands: Photo: NPS |

As the large ice sheet that capped the North American continent receded, Lake Otero evaporated and the land became desert scrubland and dunes.

|

| Lake Otero as it began to dry; Illustration: Karen Karr Studio |

About 4,000 years ago, Archaic People started to cultivate wild Indian rice grass and establish small villages.

|

| Hearth mounds; Photo: Western National Park Assn. |

Their hearth mounds, the remains of prehistoric fires containing charcoal and ash, are found within the dunes. When gypsum is heated to 300°F it becomes a plaster that hardens when moisture is added and subsequently evaporates. The plaster cements these hearths in place, preserving them for thousands of years.

The Jornada Mogollon Peoples lived in the area from about the year 200 to 1350. They made pottery, lived in adobe houses and farmed.

|

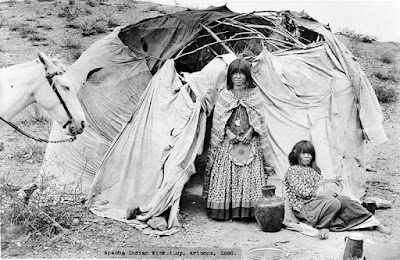

| Apaches; Photo: Have Fun with History |

Over 700 years ago, bands of nomadic Apaches followed herds of Bison from the Great Plains to the Tularosa Basin, living in temporary encampments of wickiups and teepees. The Apaches had established a sizable territory in southern New Mexico by the time European explorers arrived.

They fiercely defended their homeland against the encroachment of colonial settlers. Apache groups, led by Victorio and Geronimo, fought with settlers and Buffalo Soldiers. The Battle of Hembrillo Basin in 1880 took place on what is now White Sands Missile Range. Ultimately, the Apaches were forcibly removed from their homelands to the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation 100 miles northeast.

|

| Present-day Mescalero Apaches; Photo: New Mexico Magazine |

Spanish colonists established salt trails in 1647 to connect the Alkali Flats salinas (salt pans) with the Camino Real in El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juárez) and silver mines in Durango, Mexico, because salt is fundamental for silver processing.

|

| Salt pans; Photo: The American Southwest |

Expeditions using mule-drawn carts with military escorts would travel a few times a year to the salinas to collect the valuable mineral. Hispanic populations throughout the Spanish colonial and Mexican periods were allowed to freely gather salt, which was considered public property. Texan-American settlers, however, made private claims to the land for profit.

James Magoffin held a title to the salt flats north of Lake Lucero but had been unsuccessful in collecting fees for salt gathering. In 1854, using military force, he intercepted a salt-gathering expedition and fatally wounded three members. In response, the courts dissolved Magoffin's claim to the salt flats and established a precedent for free public access to salt deposits.

While a Spanish colony was established to the north around Santa Fe, the Tularosa Basin was generally avoided until the 19th century because of the Apache presence and the lack of reliable water sources.

Hispanic families started farming communities at Tularosa in 1861 and La Luz in 1863. The villagers mixed water with sand from the dune field to plaster the adobe walls of their homes. The white color was both decorative and functional, deflecting the heat of the summer sun.

In the 1880s, heavy rainfall turned Tularosa basin into lush grassland that attracted goat, sheep and cattle grazers, predominately from Texas. Cattle drives pushed into the Basin and ranching became the dominant economy for the next 60 years.

In 1897, the Lucero brothers, Jose, Felipe and Estevan, began ranching on the south shore of the lake that would eventually bear their name. By 1940, the family's holdings covered 31 square miles. Shortly afterward, the National Park Service took over ownership of the Lucero properties with appropriation of Lake Lucero and Alkali Flat. Remnants of the Lucero Ranch, including stock pens, watering troughs, a water well and a fallen windmill, are still there and can be seen on occasional Ranger-led tours.

At the beginning of the 20th century, discoveries of oil, coal, silver, gold and other precious minerals sparked a mini-mining boom, with 114 people filing mineral claims on about 16 square miles of Lake Lucero. Few of the claims were developed, except some salt mining and a plaster of Paris plant.

The idea of creating a National Park to protect White Sands dates to 1898, but the plan failed because it included a game hunting preserve that conflicted with the idea of preservation held by the Department of the Interior.

From 1912 to 1922, New Mexico Senator Albert B. Fall (later Secretary of the Interior) proposed legislation to create a year-round National Park that included four geographically separate and diverse areas – a portion of the Mescalero Indian Reservation, part of the dune field, a volcanic area that is now El Malpais National Monument and the shoreline of Elephant Butte Reservoir.

National Park Service Director Stephen Mather criticized the proposal as having "disjointed boundaries, lack of spectacular scenery and questionable usage." The National Parks Association and the Indian Rights Association opposed it because of the appropriation of Reservation land and the possibility of industrial usage. The bill failed.

During the 1920s, Alamogordo businessman Tom Charles promoted the economic benefits of protecting the White Sands formation and mobilized local support to build an improved state route between Las Cruces and Alamogordo, passing the southern edge of the dune field. He lobbied to have the dunes declared a National Park but was advised that National Monument status would be easier to obtain.

|

| Moon over White Sands |

In 1933, President Herbert Hoover designated White Sands National Monument and Charles became the first custodian of the Monument.

|

| Visitor Center detail |

The Visitor Center, a comfort station, three Ranger residences and three maintenance buildings were built in 1936-38 as a Works Progress Administration project.

The original eight adobe buildings and other structures were designated the White Sands National Monument Historic District when they were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

The principal architects, Lyle E. Bennett and Robert W. Albers also designed NPS buildings at Casa Grande and Bandelier National Monuments.

Bennett designed the distinctive picnic table shelters at White Sands, the Painted Desert Inn at Petrified Forest and buildings at Carlsbad Caverns and Mesa Verde National Parks.

Completely surrounded by White Sands Missile Range and Holloman Air Force Base, the Park has always had an uneasy relationship with the military. Errant missiles sometimes fall within Park boundaries and air traffic disturbs the tranquility of the area.

|

| Missile launch; Photo: US Army |

The missile range and base were established after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Operations continued after World War II and throughout the Cold War. Flight training missions continue over the dune field and the Park sometimes closes for missile tests.

When we visited, we found out that the trinity site where the original atomic bombs were tested would be open for a tour the next day.

Between 1969 and 1977, Oryx were released on the missile range and in the Tularosa Basin by the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish for hunting. With no natural predators, Oryx entered the Park and competed with native species for forage. Thousands still reside on the missile range and annual hunts have been held since 1974 to control and stabilize the population.

NPS built a 67-mile-long boundary fence in 1996 to keep Oryx out.

In 2018, U.S. Senator Martin Heinrich introduced a bill to designate White Sands a National Park with significant local, national, Native American and military support. The bill was opposed, however, by Otero County commissioners, who were concerned about increased visitation and potential affects on film-making, a big revenue generator in the area. After some concessions and adjustments, the National Monument became a National Park in 2019.

White Sands National Park has a cold semi-arid climate. The warmest months are April through October when the average high temperature reaches or exceeds 79°F. Afternoon temperatures in June and July average around 97°F. The highest recorded temperature was 111°F in 1981 and 1994. The cooler months are November through March when the average low temperature is below 32°F and the daily mean temperature is in the range 39°F to 52°F. The lowest recorded temperature was −25°F in 1962.

|

| It was warm, but pleasant when we visited |

Lake Lucero is normally a dry lakebed, but rain and snowmelt from the surrounding mountains and upwelling from deep groundwater within the basin periodically fill it with water containing dissolved gypsum. When filled, the lake covers about 10 square miles at a depth of 2 to 3 feet. As the water evaporates, small selenite crystals about 1 inch in diameter form on the surface of the lake. The ground in the Alkali Flat and along Lake Lucero's shore is also covered with selenite crystals that measure up to 3 feet long. There are occasional Ranger-led tours of the lake, but they must be booked a month in advance. Obviously, we didn’t go.

White Sands contains various forms of dunes. Dome dunes are found along the southwest margins of the field, transverse and barchan dunes in the center of the field and parabolic dunes along the northern, southern and northeastern margins. Toward the western side of the dune field, the dunes are more than 50 feet tall and they become progressively smaller toward the eastern edge, until they come to an abrupt stop at the eastern boundary. Throughout the dunes, water is only a few feet from the surface and very salty, but toward the western edge of the dune field, the water is older and even saltier.

|

| Vegetation hanging on |

The plants at White Sands stabilize the leading edges of the dunes, providing food and shelter for wildlife. Humans have made extensive use of the dune field’s native plant life for food, tea, cloth, medicine, rope, matting, sandals, baskets, hair tonic, dye and soap.

The Park’s drought-tolerant plants are able to survive in temperatures that range from sub-freezing to over 100°F and can take the high concentrations of salt. Cane cholla and other cacti, as well as desert succulents like the soaptree yucca, store water through the hot summers and dry winters, blooming in the spring. Desert grasses provide food for many tiny animals, such as Kangaroo Rats.

More than 600 invertebrates, 300 plants, 250 birds, 50 mammals, 30 reptiles, seven amphibians and one fish species inhabit White Sands National Park, including at least 45 endemic species, of which 40 are moths. As one would expect, many of White Sands’ critters are white or off-white to blend with the environment. Most of the animals are nocturnal (drat! since the Park is closed at night). We saw nada.

White Sands is the most visited NPS site in New Mexico, with about 600,000 visitors each year.

I gotta admit that our energy level at this point was flagging. Too much driving, too few animals to photograph, too much heat and not enough pretty skies. Although we were going to return to White Sands for sunrise, we didn’t, deciding instead to just head on to Albuquerque on our route home.

A Swift Trip Home

On our final night in Albuquerque, we did something completely different than the rest of the trip.

Caty had been very sad that she had not tried early on the get tickets to see Taylor Swift and had therefore missed her chance (unless Taylor decides to mount a second U.S. wave of concerts). So, Caty bought us tickets to see Taylor Swift: The Eras Tour, a film documenting the record-breaking Eras Tour.

|

| Something fun to do |

Originally, we were going to go in the evening, even discussing if we wanted to wear costumes like so many attendees are doing. We didn’t. And, then, because we got to Albuquerque pretty early, we decided to make it a movies day. We saw My Big Fat Greek Wedding 3 (sort of cute, nothing compared to the original.

Then, we changed our tickets to a late afternoon screening of Eras. Instead of the pandemonium we expected, we had an almost-private screening. We were alone until the right as the film started, when another couple came in.

The Eras Tour, Swift’s sixth headlining concert tour, spanned more than three hours with a set list of 44 songs divided into 10 distinct acts that conceptually portray her ten studio albums released over the past 17 years. The critically acclaimed tour created unprecedented ticket demand and fan frenzy. The concert tour has grossed $2.2 billion.

The film includes almost the entire concert (six songs were cut) and comprises footage from three shows at SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles. It was fantastic, especially considering that it was produced in about two months. It was fun to hear the songs and see the costumes, most of which were bejeweled (I have heard the five-figure costs of some). During the concert, Swift has 13 costume changes.

Different concerts had different versions of the basic collection, primarily different colors, although her Speak Now ballgowns were quite different from each other. In all the tour sported 28 different outfits. I love sparkly things, so this show delivered! The film has already made $125 million.

Guess what! I’m a Swiftie now.

And, on that high note, we headed home. Another eclipse and two new Parks for Caty.

Trip date: October 12-21, 2023

No comments:

Post a Comment