|

| Mandatory sign shot; Photo: Caty Stevens |

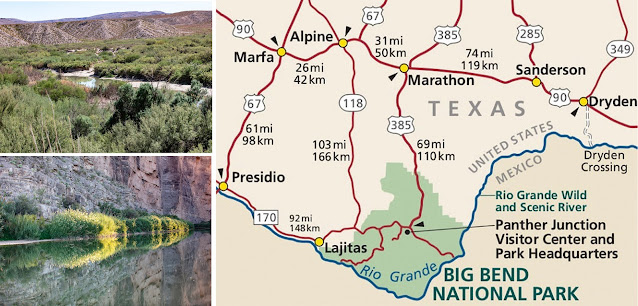

Big Bend National Park gets its name from its location: the big bend in the Rio Grande River along the southern border of Texas with Mexico. It is the largest protected area of Chihuahuan Desert topography and ecology in the United States.

|

| Named for the Rio Grande River bend |

It is one of the largest, most remote and least-visited National Parks in the contiguous United States. In the 10-year period from 2009 to 2019, an average of 377,154 visitors entered the park per year. To compare, Great Smoky Mountains National Park sees almost 13 million people a year and the Grand Canyon, 4.73 million.

|

| Desert vista |

Despite its harsh desert environment, the Park protects more than 1,200 species of plants (including 60 cactus species), more than 450 species of birds, 56 species of reptiles, 75 species of mammals and 3,600 insect species. The variety of life is largely due to the diverse ecology and changes in elevation between the dry, hot desert, the cool mountains and the fertile river valley.

|

| CW: Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Northern Mockingbird, Lincoln's Sparrow |

Most of animals are not visible in the day, particularly in the desert. The Park comes alive at night, with many of the animals foraging for food. About 150 Mountain Lion sightings are reported per year, despite the fact that only two dozen live in the park. Birds and animals include Coyotes, Kangaroo Rats, Greater Roadrunners, Goldens, Gray Foxes, Javelinas, Black-tailed Jackrabbits and Mexican Black Bears. Plans to reintroduce the Mexican Wolf were rejected in the late 1980s by the State of Texas.

|

| Secretive Greater Roadrunner |

With all that, we saw very few birds or animals on our visit, except Greater Roadrunners.

|

| We saw at least 20! |

We did have a close call driving after dark with two Mule Deer with humungous antlers that were standing right beside the winding road. And, then one crossed right in front of my car. Fortunately, I was hyper aware and saw them in plenty of time.

At night, we also saw about a dozen Lesser Nighthawks sitting on the road. We narrowly missed hitting a few. Apparently, according to the Rangers, they are attracted to headlights as they search for bugs by the road.

When most of the critters come out at night, you have to drive carefully.

|

| Milky Way; Photo: Caty Stevens |

We were really looking forward to shooting the Milky Way, but, even though we could see part of it, the bright part was below the horizon. I didn’t get a single worthy photo.

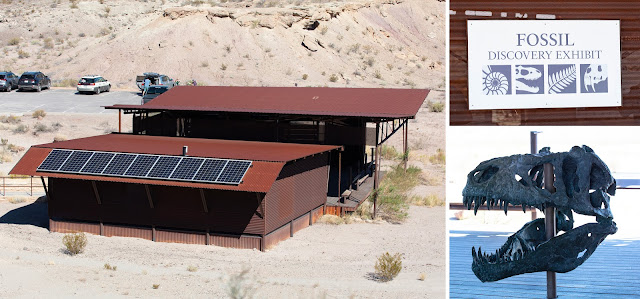

Big Bend has a rich cultural history, from archeological sites dating back nearly 10,000 years to more recent pioneers, ranchers and miners. Geological features in the Park include sea fossils and dinosaur bones, as well as volcanic dikes. There is a lovely new exhibit, the Fossil Discovery Exhibit, showcasing fossils and bones found at Big Bend. Many of the items shown were found within the past 10 years.

|

| Fossil Discovery Exhibit |

Paleontologists began working in Big Bend as early as 1907, with the discovery of sharks and ammonite fossil, reflecting the fact that the area used to be under the ocean. As the land uplifted, the animals inhabiting it included dinosaurs, amphibians, early carnivorous mammals and river creatures.

The first museum built to display fossils at the Park burned down in 1941, destroying mammoth teeth and saber tooth cat fossils. A new exhibit opened in 1957, displaying fossils of Hyracotherium, a horse ancestor, and Coryphodon, a large hippo-like animal that lived about 55 million years ago. In 1990, the fossils were replaced with replicas and the museum was overhauled in the 2000s. The Fossil Discovery Exhibit opened in 2017, replacing the previous Fossil Bone Exhibit. The multi-room shelter covers 130 million years of geologic time represented in the Park.

|

| Big Bend a long time ago; Illustration: NPS |

The huge Park encompasses an area of 1,252 square miles, including 118 miles of the Rio Grande.

The Chisos Mountains, “sky islands” surrounded by desert, are fully contained within the Park, making them the only mountain range in the United States to be solely within a National Park.

|

| Chisos Basin |

Packing for this trip was tricky because, whereas it was fall in Colorado, Wyoming and Nevada, Big Bend’s climate in October has dramatic contrasts. Well, it has contrasts all the time because its elevation ranges from 1,800 feet along the river to Emory Peak in the Chisos Mountains at 7,832 feet.

We experienced warm to slightly cool temps in Great Basin, mid-90s in Vegas and high 80s in Big Bend, cooling a bit at night. While the 80s sounds pleasant, in Big Bend it is hot, most likely due to the extremely dry and clear sky that provides no sun protection.

|

| Volcanic debris |

|

| Deep canyons with nearly vertical walls |

We never felt much like hiking because most of Big Bend is scrub with little shade. Our one attempt to hike was a bust, so we did mainly viewing from the road.

The southern part of Big Bend has three spectacular deep canyons – Santa Elena, Mariscal and Boquillas – that were cut into the rock cliffs by the Rio Grande.

We arrived at Boquillas at mid-day and the caution signs about people dying in mid-day heat was enough to make us decide to not hike in. I have done it before, so I was fine with that.

|

| I hiked in in 2014 |

Mariscal can be reached only by raft. We went to Santa Elena twice. The night we arrived, it was backlit by the setting sun …

|

| Santa Elena Canyon |

It took us a bit longer to get there than planned because we spent some time photographing some beautiful horses right by the road. We initially thought they were wild, but later decided that they were domestic horses because the area also has lots of grazing cattle.

|

| Regardless, they were beauties (there was also a colt that I didn’t capture) |

We went back early the next morning to try to catch sunrise …

|

| Morning light |

Unfortunately, we didn’t make it in time to see the cliffs light up, if they did at all. And, with no clouds in the sky, the sunset and sunrise were rather flat.

|

| The wall on the Mexican side |

We deeply regret not stopping to photograph the twin peaks called Mule Ears the first night, mistakenly thinking that we’d get better light the next day. It was never as pretty as what we saw driving by in the late evening.

|

| Mule Ears in 2014 and 2017 |

We planned to hike Santa Elana, which requires crossing an area that is sometimes a back channel off the Rio Grande. The first time I went to Big Bend, the river was high and crossing would require wading through very deep water. The second time I went, Scott and I crossed over and walked right onto the trail.

This time, the river had dramatically eroded the bank. After watching numerous hikers struggling to climb the 10-or-so-foot-tall bank, we decided it wasn’t worth risking our lives on the slippery sand bank and instead we just poked around before doing some more sightseeing. We saw several kayakers entering and leaving the river and wished that we had booked a float trip. I think that would be a good way to see the Park.

In Big Bend, there is a lot to see, in terms of landscape. The Park has eight different types of environment, which, in order of predominance, are desert shrubland, igneous grassland, limestone grassland, riparian vegetation, montane woodland, bare ground, developed area and surface water.

|

| Big Bend views |

There are several hot springs in the park, including the cleverly named “Hot Springs.” The springs were the first major tourist attraction in the Big Bend area, in the early 1900s long before the National Park was established. I have hiked the trail to the springs twice (and drove the white-knuckle road in and out, as well).

The first time I went, I couldn’t find the springs. When I saw them the second time, I realized they were completely submerged in the Rio Grande the first time. Caty wasn’t particularly interested in going down the open trail mid-day in the blazing sun, so we didn’t go this time.

Big Bend has five paved roads, including: a 28-mile road from the north entrance to Park headquarters (Persimmon Gap to Panther Junction); a 21-mile road that descends 2,000 feet from headquarters to the river (Panther Junction to Rio Grande Village); a 23-mile route from the western entrance to headquarters (Maverick Entrance Station to Panther Junction); a 6-mile road that climbs to 5,679 feet at Panther Pass before descending into the Chisos Basin (Chisos Basin Road); and the 30-mile Ross Maxwell Scenic Drive that leads to the Castolon Historic District and Santa Elena Canyon.

|

| We drove ’em all |

During the early historic period (before 1535) several Native American groups were recorded as inhabiting the Big Bend.

|

| There's a lot of history in the rock layers |

|

| At a wickiup; Photo: Mescalero Apache Tribe |

One of the last Native American groups to visit Big Bend was the Comanches, who passed through along the Comanche Trail on their way to and from periodic raids into the Mexican interior. These raids continued until the mid-19th century.

|

| Cabeza de Vaca: Illustration: Academia Play |

Some were searching for gold and silver; some for farm and ranch land; and others were establishing missions to convert the native peoples to Catholicism.

The Spanish built a line of presidios, or forts, along the Rio Grande in the late 18th century to protect New Spain, from which emerged present-day Mexico, from Indian incursions.

But, most of the presidios were abandoned quickly and the soldiers and settlers moved to newer presidios where the interests of the Spanish Empire were more defensible.

Eventually, the region became a part of Mexico when it achieved its independence from Spain in 1821. Mexican families lived in the area when English-speaking settlers began arriving following the secession of Texas during the latter half of the 19th century.

Following the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the U.S. Army established forts and outposts to protect migrating settlers from Indian attacks. A significant proportion of the soldiers in the late 1800s were African American and came to be called the "buffalo soldiers," a name given to them by Native Americans.

|

| Homer Wilson Ranch |

Ranchers began to settle in the Big Bend about 1880, and by 1900, sheep, goat and cattle ranches occupied most of the area. The delicate desert was soon overgrazed.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, valuable mineral were discovered, attracting settlers to work in the mines or support the mines by farming or cutting timber for mines and smelters.

Communities, including Boquillas (now in Mexico) and Terlingua (now in Texas), sprang up around the mines.

|

| Sights along Ross Maxwell Drive |

In May 1916, a raid on Glenn Springs received national attention, motivating President Woodrow Wilson to mobilize the Texas National Guard to aid federal forces along the border. A permanent cavalry camp was established at Glenn Springs in 1916 and remained until 1920.

In the 1930s, people who loved the Big Bend country began efforts to preserve it future generations. In 1933, the Texas Legislature established Texas Canyons State Park, which was almost immediately redesignated as Big Bend State Park. In 1935, the United States Congress passed legislation to enable the acquisition.

|

| Big Bend became a National Park 1944 |

As I mentioned, Chisos Mountains Lodge was home for one night. The room was fine, if unremarkable. The restaurant hours aren’t particularly conducive to sightseeing in the huge Park, so we ate dinner in our room (which had a microwave and refrigerator). We left too early the next morning for breakfast, but did grab a lunch there. I had some good smoked gouda/red pepper soap and a so-so Caesar salad and Caty had a delicious black been burger. That’s what I will have if I ever go back.

|

| Dramatic landscape |

The next night, we glamped at Camp Elena, which, at 10 miles away from the Park boundary, is one of the closest private places to stay near Big Bend.

|

| Our "tent" |

Getting there required driving a winding, rutted gravel road with a couple of major hills. It was fine, but I am so glad we decided to check-in in the afternoon rather than late at night. Finding it in the dark would be difficult.

We drove into Terlingua Ghost Town and picked up barbeque and Margaritas-to-go (yes!). Quite frankly, all the driving was finally getting to me, so we just chilled in our nicely appointed tent-room. It had a fire pit that we were just too lazy to fire up, but I did sit on the deck as the sun set and the stars came out. We even saw a couple of shooting stars. The room had a telescope, but we never dragged it out to the deck (I said I was tired and I did drink a Margarita!).

Being way out there, I expected to see some critters but, not so much.

In fact, "not so much" captures our experience in the Park, as well. Animal and bird spottings were few and far between (literally; it's a big Park).

|

| Left: Mourning Doves and Vesper Sparrow; Middle: Chihuahuan Greater Earless Lizard; Right: Desert Cottontail, Pinacate Beetle |

As I mentioned, we saw hardly anything, except Roadrunners. And we had several really good encounters.

Greater Roadrunners

|

| Is it "meep, meep" or "beep, beep?" |

A long-legged bird in the Cuckoo family, Greater Roadrunners live in the Southwestern United States and Mexico.

They can be found from 200 feet below sea level to 7,500 feet above, but rarely above 9,800 feet. They occupy arid and semiarid scrubland, with scattered vegetation generally less than ten feet tall.

|

| Lesser Roadrunner, Photo: eBird |

Greater Roadrunners are also called Chaparrals, Ground Cuckoos and Snake Killers.

Their cousin, the Lesser Roadrunner, lives on the west coast of Central America from northern Mexico south to Nicaragua, with another population on the Yucatan Peninsula.

Prehistoric remains indicate that up until 8,000 years ago, the Greater Roadrunner was found in sparse forests rather than scrubby deserts; only later did it adapt to arid environments. Due to this, along with human transformation of the landscape, it has recently started to move northeast of its normal distribution.

Roadrunners are good-sized birds: 20-24 inches long with a 17-24-inch wingspan and standing up to almost a foot tall. Roadrunners are predominantly brown and white, but they have iridescence on their long tail feathers. They have a crest of brown feathers that they can raise and lower and a long stout beak with a hooked tip. Roadrunners have a bare patch of red/orange and blue/white skin behind each eye; the red/orange part often hidden by feathers.

|

| Close-up of the crest and face |

They have four toes on each: two face forward and two face backward.

Although capable of limited flight, Roadrunners spend most of their time on the ground and can run at speeds up to 25 mph, often maintaining speed over long distances. While running, a Roadrunner holds its head and tail parallel to the ground and uses its tail as a rudder to help change direction. It prefers to run in open areas, such as roads, packed trails and dry riverbeds rather than dense vegetation.

|

| Running |

Feeding mainly on small animals, such as insects, spiders (including black widows and tarantulas), centipedes, scorpions, mice, lizards and small snakes (including venomous ones), they use their speed to run down prey.

|

| Eating a Grasshopper |

They also eat birds (including hummingbirds).

They are opportunistic and are known to feed on carrion (no speed needed here except to avoid cars when eating roadkill).

|

| In the sun |

Greater Roadrunners are monogamous, forming a long-term bond and defending territory together. In spring, they work together to build a thorny nest low in a cactus or a bush. The female lays three to six eggs, which hatch in 20 days. The chicks fledge in another 18 days.

Pairs may occasionally rear a second brood when there is an abundance of food in rainy summers.

Like some other cuckoos, they occasionally lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, such as the Common Raven or Northern Mockingbird.

Because they live in harsh climates, they use thermoregulation to reduce dehydration and overheating. During the hot season, they are active mostly from sunrise to mid-morning and late afternoon to evening. They rest in the shade during the hottest part of the day and reduce excess heat by releasing water vapor by breathing or through the skin. Panting accelerates this action.

At night, they reduce energy expenditure by more than 30 percent, lowering body temperature from 104°F to 93°F. They warm up by turning perpendicular to the ground, back turned towards the sun and wings apart. Then, they ruffle their black back and head feathers, exposing black skin, allowing both skin and feathers to absorb heat.

Roadrunners can stay in this posture for two or three hours and, when it is chilly, several times a day. In winter, they also escape cold winds by hunkering down in dense vegetation or among rocks.

|

| Cool shadows |

Some Pueblo Native American tribes, including the Hopi, believed the Roadrunner provided protection against evil spirits. In Mexico, some said it brought babies, as the Stork was said to in Europe. Some Anglo frontier people believed Roadrunners led lost people to trails.

The Greater Roadrunner is the state bird of New Mexico and the mascot of California State University, Bakersfield and the University of Texas at San Antonio.

And, of course, there’s the famous Road Runner who habitually outsmarts Wile E. Coyote.

|

| Illustration: Looney Tunes Trip date: October 12-21, 2023 |

No comments:

Post a Comment