|

| Muir Woods is green and leafy |

The plan was to drive to Mill Valley and drop off our

trailer at our hotel, then go on to Muir Woods. The next day we would head to

Lassen Volcanic National Park. But a few things happened.

First, since we didn’t like our campsite at Sequoia and

because the weather was dicey, we left the evening before we were scheduled to

drive to Muir Woods and stopped for the night in Fresno. With this slight

change, I went online to check how early Muir Woods opens (its day-use only) and was shocked to

discover that reservations are now required for parking (or, you can take a

shuttle bus from a distant location). Reservations! Yikes, I had not made any.

So, I very quickly logged on and found that many slots were taken for the next

day, so I had to settle for 4:00 p.m. and make plans for the morning.

|

| Reservations are now required |

When we got to Mill Valley, we were not able to check in

early and we were not allowed to park the trailer in the hotel parking lot (nor

were we allowed to use a restroom). But, they did give us a sticker and allowed

us to park by the service road by the hotel. I honestly can’t really recommend

the Travelodge in Mill Valley; I should have booked at the much nicer (and more

expensive) Best Western.

|

| Mmmmmm ... Dungeness crab |

Surely, we could find a nice restaurant with crab.

Surely.

Not so much.

Surely.

Not so much.

We looked around Mill Valley and didn’t see anything (plus,

the setting wasn’t that pretty). So, we decided to drive up to Point Reyes

National Seashore and find a place on the way. Online reviews led us to the

Coast Café in Bolinas. It was a pretty

drive along very winding roads that took us through Stinson Beach (we also

tried to find a restaurant there) and past the Bolinas Lagoon, where we stopped to

photograph a huge haul out of Harbor Seals (you can read about Harbor Seals in

my recent Iceland post).

|

| Harbor Seals and Pacific Brown Pelicans |

We also saw Pacific Brown Pelicans (lots of them) …

|

| Pacific Brown Pelicans on the wing |

… Turkey Vultures (also lots of them) …

|

| Turkey Vultures |

… and, Long-billed Curlews …

|

| Long-billed Curlew |

|

| Scenes from Bolinas |

Unfortunately, the sun decided to disappear just as I started taking pictures.

But, Scott was hungry, so on to Bolinas, which was the

hippiest-looking hippie town I have been in in a long time.

The Coast Café was

a bit of a bust.

They had no crab and, despite a sign touting halibut, we had to push to see if they really had any. At first, “no,” then a begrudging “yes.” The food was OK, but the waitresses’ sour mood ruined it. I got a sense that it

is a local’s place and tourists are barely tolerated.

Point Reyes National Seashore

Then, on to Point Reyes National Seashore, a 71,028-acre park preserve located on the Point Reyes Peninsula in Marin County. Established in 1962 (the year Bolinas got its vibe), it’s a nature preserve that still includes some private farms and ranches that have commercial cattle grazing.

Then, on to Point Reyes National Seashore, a 71,028-acre park preserve located on the Point Reyes Peninsula in Marin County. Established in 1962 (the year Bolinas got its vibe), it’s a nature preserve that still includes some private farms and ranches that have commercial cattle grazing.

|

| Point Reyes National Seashore |

When we arrived we learned, much to my dismay, that the

Point Reyes Lighthouse was closed for renovations. This, of course, is the bane

of visiting the west coast: lighthouses seem to be closed for restoration more

often than they are open. Well, at least, we didn’t make the long drive out to

the point before we discovered the closure.

|

| Point Reyes Lighthouse in 2013 |

Instead, we went to Limantour Beach, a narrow sandy beach

reached via a trail through some wetlands.

|

| Limantour wetlands |

The day had gotten rather windy and

somewhat gloomy, but that seemed appropriate for that beach.

|

| Limantour Beach |

From the boardwalk that led to the beach, I watched a number

of birds flit to and fro, but was able to capture only a few with my camera – a

female Common Yellowthroat ...

|

| Common Yellowthroat |

… a very photogenic White-crowned Sparrow …

|

| White-crowned Sparrow |

… and the ubiquitous California Gull …

|

| California Gull |

One of the most interesting things about Point Reyes is that

the peninsula is geologically separated from the rest of Marin County and

almost all of the continental United States by a rift zone of the San Andreas

Fault, about half of which is sunk below sea level and forms Tomales Bay. The

fact that the peninsula is on a different tectonic plate than the east shore of

Tomales Bay produces a difference in soils and vegetation. It’s not particularly noticeable, but it

is cool.

On to Muir Woods

But, the clock was ticking. We had to get to our parking appointment at Muir Woods. As I mentioned, the drive is winding – and steep.

But, we still made it a bit early and wondered if we would be turned away until 4:00. p.m.

|

| Muir Woods |

We approached from Point Reyes, which must be the opposite direction that most

people arrive because there was no signage indicating where to go to park. As a

result, we overshot the parking lot and had to go back. No, they didn’t make us

wait, but we did have to walk from an overflow lot. No big deal!

Muir Woods National Monument is named after naturalist John

Muir, who gets mentioned a lot when discussing National Parks and Monuments. Perhaps

I should take a minute to talk about him (most of the information below is from Wikipedia).

John Muir

John Muir (April 21, 1838 – December 24, 1914) was an

influential Scottish-American naturalist, author, environmental philosopher,

glaciologist and early advocate for the preservation of wilderness in the

United States of America. He is often referred to as the "Father of the

National Parks."

|

| John Muir is America's most prominent naturalist |

His letters, essays and books describing his adventures in

nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada, have been read by millions. His

activism helped preserve the Yosemite Valley, Sequoia National Park and

many other wilderness areas.

The Sierra Club, which he co-founded, is a

prominent American conservation organization. In his later life, Muir devoted

most of his time to the preservation of the Western forests.

Born in East Lothian, Scotland, Muir’s earliest

recollections were of taking short walks with his grandfather when he was three.

His "love affair" with nature may have been in reaction to his strict

religious upbringing in which his father believed that anything that distracted

from Bible studies was “frivolous and punishable.”

In 1849, Muir's family immigrated to Wisconsin. When he was

22, he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin Madison where he attended

classes for two years but never advanced higher than a first-year student because

of his diverse selection of courses. Although he never graduated, he learned

enough geology and botany to serve him in his examination of nature.

|

| A young Muir |

In 1864, he moved to Ontario where worked at a local

mill/factory and spent his free time exploring woods and swamps and collecting

plants around the southern reaches of Lake Huron's Georgian Bay. In 1866, moved

to Indianapolis to work in a wagon wheel factory.

In early 1867, a tool he was

using slipped and cut the cornea in his right eye, which also caused his left eye to sympathetically fail. He was confined to a dark room for six

weeks to regain his sight, worried about whether he would end up blind. When he

didn’t, he “saw the world – and his purpose – in a new light.”

He decided to follow

his dream of exploration and study of plants. In 1867, Muir undertook a walk of about 1,000 miles from

Kentucky to Florida, which he recounted in his book A Thousand-Mile Walk to

the Gulf. He had no specific route chosen, except to go by the

"wildest, leafiest and least trodden way I could find.”

When Muir arrived

at Cedar Key, he began working in a sawmill and contracted malaria. The next year, he traveled to Cuba and studied shells,

plants and flowers. Then, he sailed to New York City and booked passage to

California where he served as an officer in the United States Coast Survey.

Finally settling in San Francisco, Muir immediately left for

a week-long visit to Yosemite, a place he had only read about. He built a small

cabin along Yosemite Creek, designing it so that a section of the stream flowed

through a corner of the room so he could enjoy the sound of running water. He

lived in the cabin for two years and wrote about it in his book, First

Summer in the Sierra.

|

| Muir's sketch of his Yosemite cabin |

Over time, he became a "fixture" in Yosemite

Valley, respected for his knowledge of

natural history, his skill as a guide and his vivid storytelling. Visitors to

the Valley often included scientists, artists, and celebrities, many of whom

made a point of meeting with Muir.

|

| John Muir |

Muir became (correctly) convinced that glaciers had sculpted many of the

features of the Yosemite Valley and surrounding area, an idea in stark

contradiction to the accepted contemporary theory promulgated by Josiah

Whitney, head of the California Geological Survey. He attributed Valley formation to a catastrophic earthquake. Whitney tried to discredit Muir by

branding him as an amateur. But Louis Agassiz, the premier geologist of the

day, saw merit in Muir's ideas. In 1871, Muir discovered an active alpine

glacier below Merced Peak, which helped his theories gain acceptance.

A strong earthquake shook occupants of Yosemite Valley in

March 1872, leading those who believed Whitney's ideas to fear a cataclysmic

deepening of the valley.

Muir, who had no such fear, immediately surveyed the new talus piles

created by earthquake-triggered rockslides, leading more people to believe his

ideas about the formation of the valley.

|

| Muir loved botany |

In addition to his geologic studies, Muir also investigated

Yosemite's plant life. In 1873-74, he made field studies

along the western flank of the Sierra on the distribution and ecology of

isolated groves of giant sequoia.

In 1876, the American Association for the

Advancement of Science published Muir's paper on the subject.

Not content to restrict his studies to Yosemite, Muir traveled

to Alaska, as far as Unalaska and Barrow and, in 1879, was among the first Euro-Americans to explore Glacier

Bay. Muir Glacier was later named after him.

|

| Left, Muir in Glacier Bay; Right, Muir Glacier in 1994 |

Muir married Louisa Strentzel in 1880 and went into business

with his father-in-law managing the orchards on the family 2,600-acre farm in

Martinez, California. They had two daughters.

|

| Daughters Helen and Wanda on the porch with Louisa (Louie) and John Muir |

He returned to Alaska in 1880 and, in 1881, was with the

party that landed on Wrangel Island on the USS Corwin and claimed that island

for the United States. He documented this experience in journal entries and

newspaper articles, later compiled and edited into his book The Cruise of

the Corwin. In 1888, after seven years of managing the Strentzel fruit

ranch, his health began to suffer. He returned to the hills to recover,

climbing Mount Rainier in Washington and writing Ascent of Mount Rainier.

|

| Muir at his desk, writing |

An ardent preservationist, Muir envisioned the Yosemite area

and the Sierra as pristine lands and thought the greatest threat to the area was

domesticated livestock, especially domestic sheep, which he referred to as

"hoofed locusts." In 1889, the influential associate editor of The

Century magazine, Robert Underwood Johnson, camped with Muir in Tuolumne

Meadows and saw firsthand the damage a large flock of sheep had done to the

grassland. Johnson agreed to both publish any article Muir wrote on excluding

livestock from the Sierra high country and to use his influence to introduce a

bill to Congress to make the Yosemite area into a National Park, modeled after

Yellowstone National Park.

|

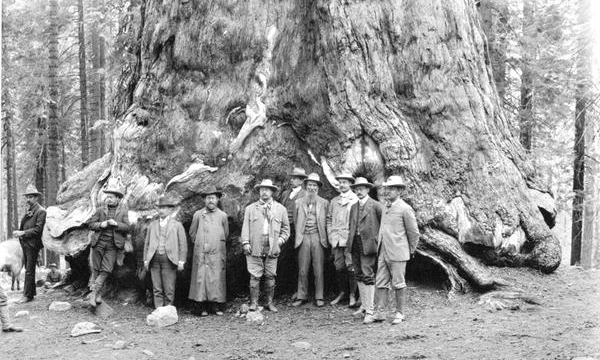

| Teddy Roosevelt and John Muir at Glacier Point in Yosemite |

In 1890, Congress passed a bill that essentially followed Muir’s

recommendations but left Yosemite Valley under state control, as it had been

since the 1860s.

In early 1892, Muir was instrumental in forming The Sierra

Club, of which he remained president until his death 22 years later.

|

| An early Sierra Club meeting, with Muir and Roosevelt in attendance |

The Sierra Club was active in creating the idea of National

Forests, in the successful campaign to transfer Yosemite National Park from

state to federal control in 1906 and in the unsuccessful fight to prevent the

Hetch Hetchy Valley from being dammed.

|

| John Muir is an inspiration to environmentalists |

In his life, Muir published six volumes of writings, all

describing explorations of natural settings. Four additional books were

published posthumously. Several books were subsequently published that

collected essays and articles from various sources.

John Muir died of pneumonia at age 76.

Muir Woods

|

| Scott at the entrance to Muir Woods |

Muir Woods, located on Mount Tamalpais in southwestern Marin

County, protects 554 acres of which 240 acres are old growth coast redwood forests, one of a few such stands remaining in the San

Francisco Bay Area.

|

| Coast redwoods |

Due to its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, the forest is regularly shrouded in a coastal fog, contributing to a wet environment that encourages vigorous plant growth.

The fog is also vital for the growth of the redwoods because they use the moisture from the fog during drought and during dry summers.

While it wasn’t foggy while we were there, the heavy overgrowth coupled with the time of day made it somewhat dim. As a result, my photos are pretty sad – and I missed a few birds.

Coast redwoods, which, in general, are slimmer but

taller than giant sequoias, grow on humus-rich loam that may be gravelly,

stony or somewhat sandy. They are almost always found on sloping ground. Although ancestors

of these trees could be found all over what is now the United States about 150 million

years ago, they can now be found only in a narrow, cool coastal belt from

Monterey County, California, to Oregon.

While coast

redwoods can grow to nearly 380 feet, the tallest tree in the Muir Woods is 258

feet. The trees come from a seed no bigger than that of a tomato.

|

| Coast redwood bark |

Most of the

redwoods in the monument are between 500 and 800 years old, with the oldest at at least 1,200 years old.

Before the logging industry came to California, there were

an estimated 2 million acres of old growth forest containing redwoods along the

coast.

By the early 20th century, most of these forests had been cut down. Just

north of the San Francisco Bay, one valley named Redwood Canyon remained uncut,

mainly due to its relative inaccessibility.

|

| A downed tree is covered with moss |

William Kent, a rising California politician who would soon

be elected to Congress, and his wife, Elizabeth Thacher Kent, purchased 611

acres of land in Redwood Canyon from the Tamalpais Land and Water Company for

$45,000 with the goal of protecting the redwoods and the mountain above them. In

1907, a water company in nearby Sausalito planned to dam Redwood Creek, thereby

flooding the valley. When Kent objected to the plan, the water company

threatened to use eminent domain and took him to court to attempt to force the

project to move ahead. Kent cleverly donated 295 acres of the redwood forest to

the federal government, thus bypassing the local courts.

|

| Muir Woods ferns |

In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt declared the land a

National Monument, the first to be created from land donated by a private

individual. The original suggested name of the monument was the Kent Monument

but Kent insisted the monument be named after John Muir.

Kent and Muir had

become friends over shared views of wilderness preservation, but Kent's later

support for the flooding of Hetch Hetchy caused Muir to end their friendship.

In 1937, the Golden Gate Bridge was completed and park

attendance tripled, reaching over 180,000. Muir Woods is one of the major

tourist attractions of the San Francisco Bay Area, with 1.2 million visitors in

2017. The reservation system is designed to lower that annual number to no more

than a million per year.

|

| Muir Woods trees, many leaning into the sunlight |

Other tree species grow in the understory of the redwood

groves in Muir Woods, including California bay laurel, the bigleaf maple and

the tanoak.

Each has adapted to the low level of dappled sunlight that reaches

them through the redwoods overhead.

The California bay laurel has a strong root

system that allows the tree to lean towards openings in the canopy.

The bigleaf

maple, true to its name, has developed the largest leaf of any maple species

allowing it to capture more of the dim light.

The tanoak has a unique internal

leaf structure that enables it to make effective use of the light that filters

through the canopy.

|

| Thick canopy |

Redwood Creek, which runs through the Park, provides a

critical spawning and rearing habitat for coho or silver salmon and steelhead,

both of which are endangered. We didn’t see much evidence of fish, but we did

see some crayfish and an unexpected Great Blue Heron that was taking advantage

of the creek to feed.

|

| Great Blue Heron |

Muir Woods is home to over 50 species of birds, which is a relatively

low number for California because the Park has few insects. We saw a Hutton’s

Vireo …

|

| Hutton's Vireo |

… a Chestnut-backed Chickadee …

|

| Chestnut-backed Chickadee |

… and some Pacific Slope Flycatchers that just wouldn’t come

into the light. We also saw a very curious Western Gray Squirrel …

|

| Western Gray Squirrel |

Bears historically roamed the area but were largely

exterminated by habitat destruction. In 2003 a male black bear was spotted

wandering in various areas of Marin County, including Muir Woods.

Muir Woods, part of the Golden Gate National Recreation

Area, caters to pedestrians and is a day-use area only. Parking is allowed only

at the entrance. Hiking trails vary in the level of difficulty and distance.

Picnicking, camping and pets are not permitted. There are no camping or lodging

facilities.

|

| Muir Woods Shuttle |

More than 80 percent of visitors arrive by car, and most of

the rest by tour bus or shuttle bus. The new parking reservation system was introduced in 2018. Marin Transit operates a shuttle on all weekends and

holidays and during select peak weekdays, providing service to Muir Woods from

Sausalito, Marin City or Mill Valley.

The shuttle costs $3.00 for riders 16 or

older. Parking reservations cost $8.00. Because there is NO cell phone service

or WiFi at or around Muir Woods, you have to download your parking reservation

or shuttle ticket in advance.

Dungeness Crab

So, we spent the afternoon in Muir Woods. But, the day was

not complete. Scott wanted Dungeness Crab.

|

| Driving across the Golden Gate Bridge from Marin County to San Francisco |

So, instead of fooling around, we drove across the Golden Gate Bridge and went to the Fisherman's Wharf area of San Francisco where we KNEW we could find crab. We were not disappointed. We looked around and decided to go to Pompeii's Grotto, where we had Dungeness Crab.

|

| Pompeii's Grotto features Dungeness Crab |

|

| Scott finally got his crab! |

A whole Dungeness Crab ...

Roasted in ...

Tomato ...

Garlic ...

White wine ...

Butter sauce ...

With some fresh lemon, San Francisco sourdough bread and red wine.

|

| Dinner |

Oh, yeah!

I wasn't quite as hungry, so I had crab cakes. Delicious.

The Dungeness Crab, which inhabits eelgrass beds and water bottoms on the west coast, typically grows up to almost eight inches across the carapace.

They are a popular delicacy, and are the most commercially important crab in the Pacific Northwest, as well as the western states generally.

The crab's common name comes from the port of Dungeness, Washington.

It turned out to be a great day with a great ending.

Did I mention whole crab roasted in tomato garlic white wine butter sauce? And wine and sourdough bread?

Did I mention whole crab roasted in tomato garlic white wine butter sauce? And wine and sourdough bread?

Trip date: July 19-August 2, 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment